![]()

SUZANNE CIANI SPEAKS WITH KRAUS

by Pat Kraus

Originally published via Undertheradar on 21st July, 2021

Pat Kraus: The upcoming festival at the Audio Foundation is focused on multichannel sound, so I’d like to first ask about the use of space and movement in your music. How were you introduced to multichannel sound, and how important is the use of space in your music?

Suzanne Ciani: I was brought up on the Buchla 200 (analogue modular synthesizer), so when I was in graduate school in Berkeley — I went there from ‘68 to ‘70 — I met Don Buchla, and when I finished my degree I went to work for him. Right from the beginning, he dealt in quadraphonic. So this was a guy who, I call him the Leonardo Da Vinci of electronic musical instrument design, because he really was a focused genius in designing interfaces. And if you think about it, there’s no reason why electronic sound shouldn’t be moving. I mean, where does it live? It’s not like you’re a cello and you’re sitting in a place, and you want it to come from that place.

Right, it’s disembodied.

It’s disembodied, and it comes alive when it moves. So there was a Buchla module called the 227, and it was a voltage-controlled quadraphonic spatial output module, and the beauty of that, of course, is that you are generating the space as you’re generating the music. That becomes important when you have rhythmic movement. Motion is rhythm, and if the movement doesn’t integrate with the rhythm, you’ve got a mess. That’s what I was brought up on, and I hit a wall when I was performing in the early '70s. I went to New York in ‘74 and I did a concert in quad in an art gallery. Then I wanted to make a career performing. And I went to the main hall, in Lincoln Centre, the theatre for classical music and opera and all that, and they wouldn’t put up four speakers.

They just refused?

They just refused.

OK. Wow.

So I started, you know my goal was to get theatres redesigned, and I worked and worked and worked, and I couldn’t get it to happen.

And we’re still basically stuck with stereo, aren’t we, at least for most home listening.

Well I think the breakthrough is happening, but it’s happening in film. You have home theatres now. And it’s odd because the film industry itself was slow to adopt stereo! I mean, I did a film in 1980, and it was mono, and all of Hollywood was mono. Then all of a sudden, everything shifted, when digital came in, this revolutionised behind the scenes production. Instead of sprocketed film they could record and synchronise with SMPTE time-code. So now they’ve pushed home theatres, and also the conduits for presenting sound are opening up, so Apple is adopting a spatial format, you have Dolby Atmos which provides a conduit if you want to release your music as spatial, so the whole system is in place now.

It seems to me that in the '70s there was a hope that electronic music technology would become more democratised and accessible. For example, synth designer Serge Tcherepnin said he hoped everyone would have an electronic music studio in their home. Do you think we’re starting to see that more now?

Yes, and I think the reason is partly cost, although kids don’t seem to appreciate that, because they’ll complain about how much something costs. I mean, you have no idea how much things used to cost! It was like: buying a car, or buying a module. There was a huge amount of desire associated with even getting this stuff back then, it wasn’t easy to get it to happen. Now you have thousands of different modules and they are relatively affordable.

What’s the story about your original Buchla being stolen in the '70s?

I have had bad luck. I had a cartage company that followed me around New York. I would do sessions, and they would pick up my Buchla, it was in five road cases, it was big. And one day they showed up at the studio and only half of it was there! It was in Times Square, and I thought oh my god, they’ve put it on the street, someone’s come along and picked it up, looked at it and thought what is this, and threw it in the East River. That’s what I imagined. And 30 years later I get a photo from Canada and the guy says “Hey, does this look familiar to you?” It turned out the engineer at the studio where I worked took it home with him, and kept it for 25 years, and then sold it. It’s like stealing somebody’s Stradivarius. It was an irreplaceable instrument that I had devoted my life to. It was my instrument. You can imagine the trauma that went with that. I still had half of it, but that wasn’t that useful. And then that half broke down.

In the last five years you’ve returned to performing live with a Buchla, this time with the modern 200e system. How did that come about?

I had moved from New York City to the coast of California. And I had returned to the piano. My first album out here was for orchestra and piano. Then I did some piano solo albums, and I started touring playing the piano. I didn’t have the Buchla, but, as luck would have it, Don Buchla lived here still and I reconnected with him.

You used to play tennis with him, is that right?

Exactly! We did that for years. Then at one point he said if you’re ever thinking of going back to this, now is the time, because he was selling the company to somebody in Australia. I was invited to play at Moogfest. Now, for most of my life Moog was considered the enemy, because they weren’t quadraphonic, they didn’t have feedback, they weren’t as performable to me. You know, I was a Buchla person. But Moog asked me if I would play in San Francisco, and I said yes, because I live so close. And that was my first comeback concert. And simultaneously, Finders Keepers from Manchester had been releasing stuff from my vault, stuff that had never been released, that I didn’t think was worth releasing, because they were recorded in a garage or wherever. And I discovered that there was a revolution going on, a renaissance.

Of modular synthesizers?

Yeah! And, oh my god, it was a dream come true for me, because the first time I did it, nobody understood it! I mean performing for people who don’t have a clue where the sound is coming from, it’s not the same.

It seems that the technologies and concepts of electronic music that were developed in the 60s are still very useful as expressive tools, and your recent work demonstrates that.

Yes, and also the reason the kids rebelled against digital is that it’s not human. It wasn’t interactive, it wasn’t warm, it wasn’t continuous, it wasn’t soft. And so I give the kids credit, because before that, our thinking about technology was that it’s a straight line forward, it gets better and better. So thank you guys for putting the brakes on and reinvestigating (analogue technology). When this started it didn’t happen, it was an unfulfilled promise, a possibility that didn’t manifest. And now it is, and so I’m really really happy.

When you began working with the modern Buchla 200e, did you approach it differently?

Here’s the philosophy behind this: When you’re working with a machine, you’re working with the machine. I complained to Don Buchla “I can’t do what I did in the '60s and '70s. It’s not as performable”. And he would look at me and say “Do something else! Don’t try to do what you did”. So my first comeback concert, I was using the 291e filter which has no directional voltage control, so you put a voltage in and it only goes up. I’ve grown to like that concert, even though it sounds nothing like what I was imagining. You play with the instrument, there are things that I’m grateful for, that I have still, and there’s things that I miss.

Suzanne Ciani: I was brought up on the Buchla 200 (analogue modular synthesizer), so when I was in graduate school in Berkeley — I went there from ‘68 to ‘70 — I met Don Buchla, and when I finished my degree I went to work for him. Right from the beginning, he dealt in quadraphonic. So this was a guy who, I call him the Leonardo Da Vinci of electronic musical instrument design, because he really was a focused genius in designing interfaces. And if you think about it, there’s no reason why electronic sound shouldn’t be moving. I mean, where does it live? It’s not like you’re a cello and you’re sitting in a place, and you want it to come from that place.

Right, it’s disembodied.

It’s disembodied, and it comes alive when it moves. So there was a Buchla module called the 227, and it was a voltage-controlled quadraphonic spatial output module, and the beauty of that, of course, is that you are generating the space as you’re generating the music. That becomes important when you have rhythmic movement. Motion is rhythm, and if the movement doesn’t integrate with the rhythm, you’ve got a mess. That’s what I was brought up on, and I hit a wall when I was performing in the early '70s. I went to New York in ‘74 and I did a concert in quad in an art gallery. Then I wanted to make a career performing. And I went to the main hall, in Lincoln Centre, the theatre for classical music and opera and all that, and they wouldn’t put up four speakers.

They just refused?

They just refused.

OK. Wow.

So I started, you know my goal was to get theatres redesigned, and I worked and worked and worked, and I couldn’t get it to happen.

And we’re still basically stuck with stereo, aren’t we, at least for most home listening.

Well I think the breakthrough is happening, but it’s happening in film. You have home theatres now. And it’s odd because the film industry itself was slow to adopt stereo! I mean, I did a film in 1980, and it was mono, and all of Hollywood was mono. Then all of a sudden, everything shifted, when digital came in, this revolutionised behind the scenes production. Instead of sprocketed film they could record and synchronise with SMPTE time-code. So now they’ve pushed home theatres, and also the conduits for presenting sound are opening up, so Apple is adopting a spatial format, you have Dolby Atmos which provides a conduit if you want to release your music as spatial, so the whole system is in place now.

It seems to me that in the '70s there was a hope that electronic music technology would become more democratised and accessible. For example, synth designer Serge Tcherepnin said he hoped everyone would have an electronic music studio in their home. Do you think we’re starting to see that more now?

Yes, and I think the reason is partly cost, although kids don’t seem to appreciate that, because they’ll complain about how much something costs. I mean, you have no idea how much things used to cost! It was like: buying a car, or buying a module. There was a huge amount of desire associated with even getting this stuff back then, it wasn’t easy to get it to happen. Now you have thousands of different modules and they are relatively affordable.

What’s the story about your original Buchla being stolen in the '70s?

I have had bad luck. I had a cartage company that followed me around New York. I would do sessions, and they would pick up my Buchla, it was in five road cases, it was big. And one day they showed up at the studio and only half of it was there! It was in Times Square, and I thought oh my god, they’ve put it on the street, someone’s come along and picked it up, looked at it and thought what is this, and threw it in the East River. That’s what I imagined. And 30 years later I get a photo from Canada and the guy says “Hey, does this look familiar to you?” It turned out the engineer at the studio where I worked took it home with him, and kept it for 25 years, and then sold it. It’s like stealing somebody’s Stradivarius. It was an irreplaceable instrument that I had devoted my life to. It was my instrument. You can imagine the trauma that went with that. I still had half of it, but that wasn’t that useful. And then that half broke down.

In the last five years you’ve returned to performing live with a Buchla, this time with the modern 200e system. How did that come about?

I had moved from New York City to the coast of California. And I had returned to the piano. My first album out here was for orchestra and piano. Then I did some piano solo albums, and I started touring playing the piano. I didn’t have the Buchla, but, as luck would have it, Don Buchla lived here still and I reconnected with him.

You used to play tennis with him, is that right?

Exactly! We did that for years. Then at one point he said if you’re ever thinking of going back to this, now is the time, because he was selling the company to somebody in Australia. I was invited to play at Moogfest. Now, for most of my life Moog was considered the enemy, because they weren’t quadraphonic, they didn’t have feedback, they weren’t as performable to me. You know, I was a Buchla person. But Moog asked me if I would play in San Francisco, and I said yes, because I live so close. And that was my first comeback concert. And simultaneously, Finders Keepers from Manchester had been releasing stuff from my vault, stuff that had never been released, that I didn’t think was worth releasing, because they were recorded in a garage or wherever. And I discovered that there was a revolution going on, a renaissance.

Of modular synthesizers?

Yeah! And, oh my god, it was a dream come true for me, because the first time I did it, nobody understood it! I mean performing for people who don’t have a clue where the sound is coming from, it’s not the same.

It seems that the technologies and concepts of electronic music that were developed in the 60s are still very useful as expressive tools, and your recent work demonstrates that.

Yes, and also the reason the kids rebelled against digital is that it’s not human. It wasn’t interactive, it wasn’t warm, it wasn’t continuous, it wasn’t soft. And so I give the kids credit, because before that, our thinking about technology was that it’s a straight line forward, it gets better and better. So thank you guys for putting the brakes on and reinvestigating (analogue technology). When this started it didn’t happen, it was an unfulfilled promise, a possibility that didn’t manifest. And now it is, and so I’m really really happy.

When you began working with the modern Buchla 200e, did you approach it differently?

Here’s the philosophy behind this: When you’re working with a machine, you’re working with the machine. I complained to Don Buchla “I can’t do what I did in the '60s and '70s. It’s not as performable”. And he would look at me and say “Do something else! Don’t try to do what you did”. So my first comeback concert, I was using the 291e filter which has no directional voltage control, so you put a voltage in and it only goes up. I’ve grown to like that concert, even though it sounds nothing like what I was imagining. You play with the instrument, there are things that I’m grateful for, that I have still, and there’s things that I miss.

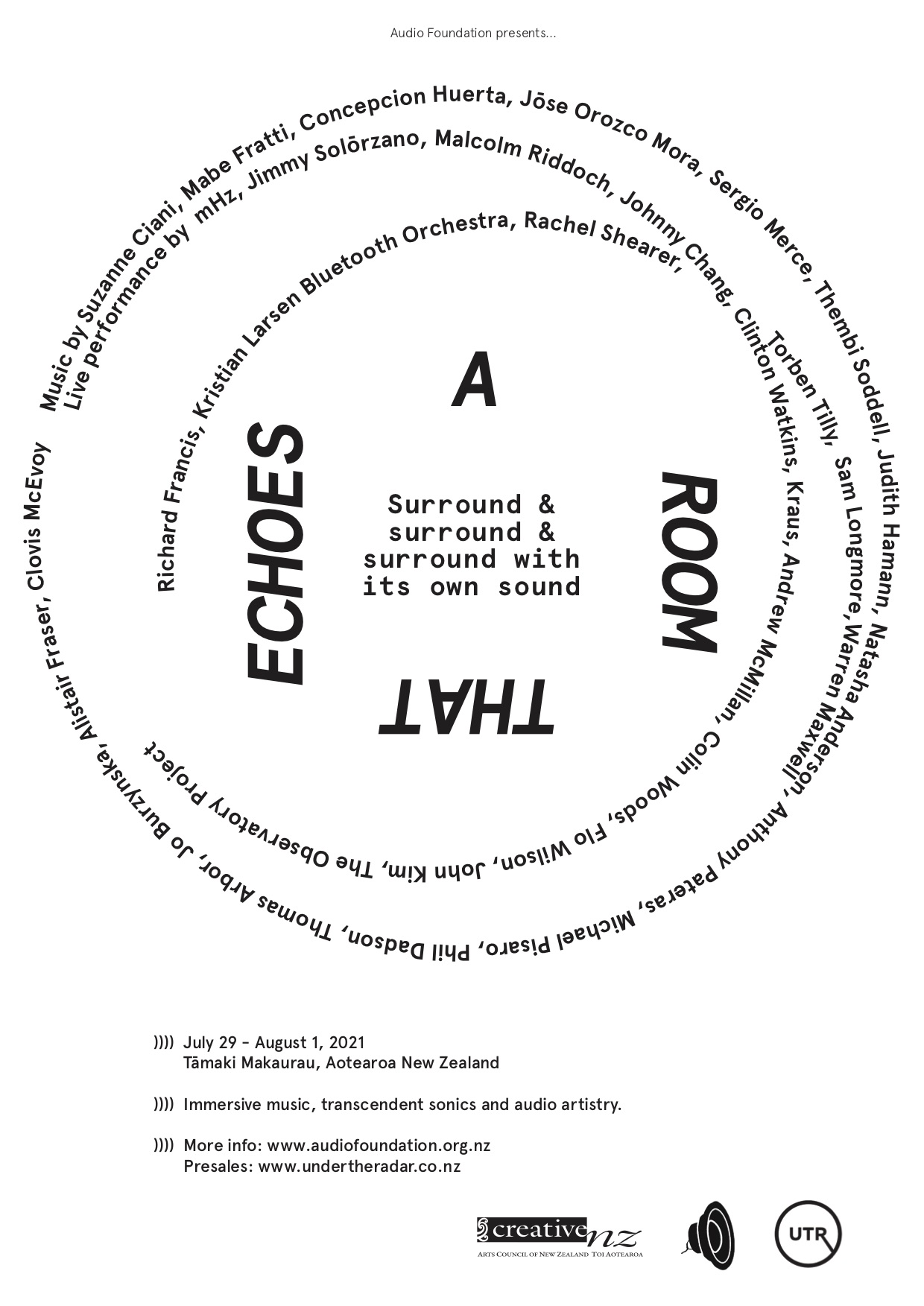

Audio Foundation’s ‘A Room That Echoes’ Festival, 2021.

Suzanne Ciani - Improvisation on 4 Sequences(live @TivoliVredenburg Utrecht)

Suzanne Ciani on 3 2 1 Contact (1980)

Suzanne Ciani On Modular Synthesis & The Buchla 200e | Composer Magazine

A Sonic Womb Pt. 1 · Suzanne Ciani

Kraus performing on Better Living TV Episode One on the 8th May 2020.

Sisters with Transistors [Official Trailer]

It’s amazing you saying there are things that you could do in the '60s and '70s that you can’t do with the current technology. That’s incredible.

That’s why I want everybody to look at Buchla’s early instruments. You know my dream actually is to go back to the 200, and the Buchla people have talked about making it. So we’ll see.

Just thinking about the size of that original 200 system, I guess one advantage of your Buchla 200e is that it’s possible for you to take it overseas to perform.

Exactly. That’s the good news. I can bring it in one suitcase, I can check it as baggage, which is a little scary, but possible. The bad news is, in the sequencer for instance, which is just one panel unit, a lot of the performance techniques that I had before involved interacting live with the sequencer, either assigning pulses, lengths, whatever, just playing that sequencer. And you can’t play a digital sequencer. “Excuse me everybody, wait, I’m just going into this menu, I’ll be five minutes...”

Before the pandemic you were touring and playing quite regularly, is that right?

Nonstop. I think for the last five years I basically lived in airplanes, and that became habitual. And now my habit is to stay home.

How have you been navigating the pandemic? I see you’ve begun to release some of your live recordings.

Because I play in quad, I have this dilemma of how to release on vinyl. So the first vinyl quad that I did, the record came with a decoder, made by Australian company Involve Audio. Lovely people doing a beautiful job with spatial encoding and decoding. The next one is coming out in November in vinyl — it was already released digitally — but we don’t have to include a decoder, because the world is now more spatial than it was a few years ago, and the decoding can happen without the special decoder.

That’s amazing. So the technology is developing quite rapidly. Are there more releases coming?

I recorded just about all the concerts, so I certainly have plenty of material to release. The stumbling block was of course the vinyl, and now that’s getting easier. I don’t know how interested people would be in hearing all these variations of this concert. The piece that I play is based on four sequences that I played in the 70s. I wrote a paper, a report to the National Endowment, it was all in there. When I came back to the Buchla, I looked at the paper, and it reminded me how to play, how you do it.

So the basic musical material that you’re using now reaches back to that mid-70s period?

Yes, it’s the same sequences I used then, but in those days sequencers were not static, because you were interacting with them. So I have a different compositional challenge now. As you know from playing these machines, it’s a process of keeping the material alive, and moving.

It’s obviously really important for you to actively perform with your Buchla, rather than just letting it play itself. But on the other hand, using any modular instrument, there’s a lot of preprogramming involved. How do you see that relationship between programming and live expression?

Well, when I perform I project my Buchla up on a big screen, so that people can see when I do this, do that, whatever, but what we love about voltage control is that the voltages are doing a lot of the work. I’m not sitting there swirling the sound around the space, but I can interact with, say, the envelope that is affecting it, so it might be a hierarchical level above. See, this was the limitation of the first understanding of the analogue modular. Switched on Bach came out, and people thought it was a keyboard instrument. And with a keyboard you do one thing, and you get one thing. That was so limiting that the keyboard became the enemy of analogue modular. It was the enemy because that’s so boring! The whole beauty of analogue is that you can orchestrate and design voltages that produce interesting levels of musical information.

Would a good analogy be that you’re conducting an orchestra, rather than playing a solo instrument?

I don’t think of it that way, I think of it, honestly, as a new language. I remember when I worked with Philip Glass in New York in 1974 or '75, and I said “Philip, you should be using a sequencer!” Because everybody’s just trying to keep up with this pattern. I think his techniques were derived, even unconsciously, from the machinery of music that was happening.

That’s interesting, because I think that people like Philip Glass and Steve Reich have influenced the current generation of electronic music.

Well this is a little aside, but when I was in New York in those early days, Steve Reich came to one of my concerts, and he said to me “They should take all these things and send them to the moon!”

Ha! OK, not open to it.

Not open to it. And then recently, I met his son Ezra Reich at a NAMM show, and he’s an electronic musician. The world changes, and it’s fascinating to be old like me, and see it in all its chapters.

As a woman in music in the late 60s / early 70s, was electronic music a path to liberation for you as a composer?

Oh absolutely! You know that film that just came out Sisters with Transistors, we were all in our little worlds, so we didn’t really know each other. But the truth is that women gravitated to this because it was self-contained, and it allowed you to do the whole thing, you could compose, you could perform, you didn’t need the infrastructure. It was very liberating, and I think because women did not have as great an investment in the normal music of the time — you know, the guitars and the drums — we were open to something new. It was a promise, it was, you know: Freedom! Power! Independence! Thank-you!

Yeah! And it’s really a fascinating subject for me, I mean, the question of why is electronics and technology so liberating for marginalized groups? I think it’s still true with electronic music, that for women, and people of colour, and queer and trans people, electronic music is this amazing way of expressing yourself on your own terms. That’s still very much true I think.

Fantastic!

Watching a film like Sisters with Transistors you might assume that women in electronic music were aware of their own history. But you’re saying you weren’t familiar with other women in the field?

Well, for instance, when Finders Keepers released the Buchla Concerts 1975, in the liner notes Andy Votel called me “the Delia Derbyshire of the Atari generation”, and I said who’s Delia Derbyshire? I’d never heard of her!

Amazing!

I didn’t know Daphne Oram! I discovered Daphne Oram when I played at Royal Albert Hall a couple of years ago. They premiered a symphony of hers that was written in the 40s, so over 70 years later she had her first performance of a piece.

What about Laurie Spiegel? You would have been in New York at the same time she was at Bell Labs. Were you familiar with her at all?

Yes, we had in common (computer music pioneer) Max Mathews, because I had studied with Max Mathews while I was still in graduate school, he came out to Stanford and I studied with him and John Chowning in a summer course at the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, so we had that in common. We bumped into each other in New York a little bit, but we were in different worlds. I was doing big studio commercial work along with my art work, so we’d see each other once in a while at the Audio Engineering Convention. But I really didn’t know anything about her. I’m just finding out now. For example, I worked with a lot of companies back then, and one of them was Eventide, and I just found out today that Laurie Spiegel also worked with them. I never knew that. So our history has been invisible, and we’re just uncovering it. And it’s so refreshing, and empowering even for me. I guess I’m a little sad that I didn’t know. For instance I found out that there was a woman who scored a Hollywood film in the 40s. Elizabeth Firestone. Well, who knew? I can’t find any information about her. Up until I found her, I thought I was the first woman to score a major Hollywood feature (The Incredible Shrinking Woman, 1981). And I want to bring her to light. I want people to know, I mean who knows what we don’t know?