Berlin Electronic Artist Jasmine Guffond Talks With Rachel Shearer

with introduction by Torben TillyOriginally published 4th March, 2019

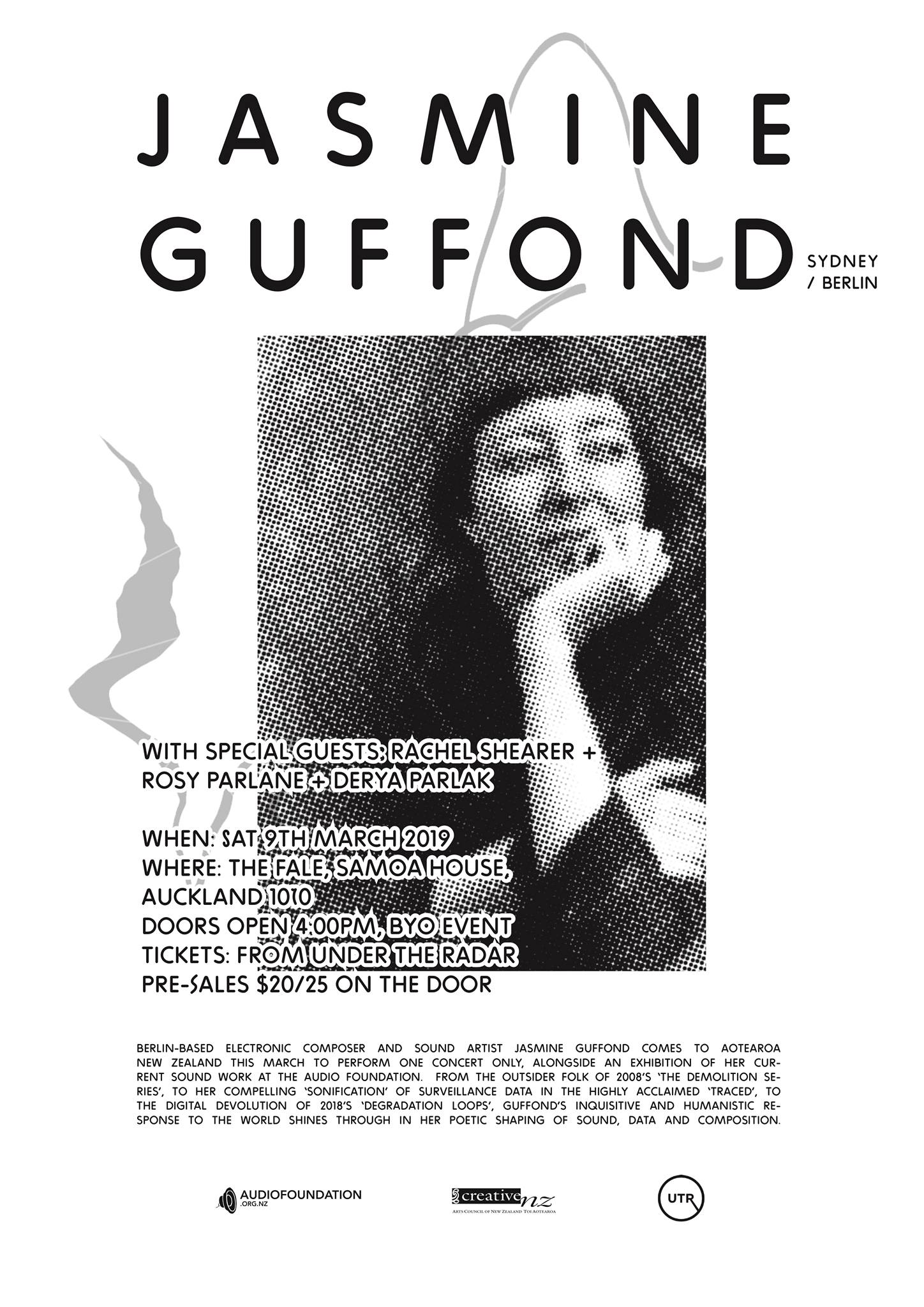

Berlin-based experimental electronic composer and sound artist Jasmine Guffond is visiting Aotearoa this week, for a not-to-be-missed concert at The Fale, Samoa House on Saturday, alongside a sound installation as part of an autumn residency at Audio Foundation in Auckland.

Jasmine's musical career has had a long and interesting trajectory from her early minimalist explorations in the duo Minit, to several albums worth of electronic-soaked outsider folk, with a return in the last few years to some very arresting and abstract electronic arrangements informed by her research into sound as a method of investigation into contemporary digital surveillance.

Interested in providing an audible presence for phenomena that usually lie beyond human perception, via the 'sonification' of facial recognition algorithms, global networks or internet tracking cookies, she questions what it means for our personal habits to be traceable, and for our identities, choices and personalities to be reduced to streams of data. Her music draws upon influences from experimental electronic, drone, techno and the avant-garde, working with abstract sound as much as traditional musical forms, and translating data into deeply engaging, compositions.

Her album Traced made significant waves in 2017, taking, as noted by the online platform Boomkat, “the textural and spatially sensitive ambient aesthetics of her previous LP, the acclaimed Yellow Bell, into palpably more paranoid and unnerving head spaces, using her filigree appreciation of electro-acoustic dynamics to convey that feeling with a subtlety which will surely resonate with anyone aware of digital surveillance technology's transition from peripheral creep to a near ubiquitous presence.”

Auckland sound artist Rachel Shearer, who is also on Saturday's lineup, explores the medium of sound through a range of practices – recording and performance of experimental music, installation, sound design, writing, research and collaborations with practitioners of moving image and performance. Her current work has been exploring analogues of structure and pattern of ecological processes through multi-channel sound installations.

Prior to Jasmine's arrival in the country this week, she connected with Rachel via email for an exchange of ideas and approaches to their individual practices, with a question from Torben Tilly [also of Minit] thrown in for good measure!

JG: What does the term 'sound artist' mean to you?

RS: I think it’s a clunky term but it has its uses. I understand the assertion that sound is already in art so there might not be a need for the term anymore, but for those of us that work with sound most of the time it becomes a handy descriptor to help someone understand your creative practice. Maybe it communicates that you approach sound as a creative material in an exploratory manner. It draws a distinction from calling yourself a musician, as that can come with certain baggage, such as being masterful on an instrument or composing with historical musical rules. Calling yourself a sound artist might indicate that you work more closely with concepts but there’s always examples of one-liner sound art works and conceptually resonant genre musical works. Calling yourself an experimental musician is equally as useful - I use both terms depending on the context and sometimes the term sound designer is more relevant.

JG: I read in a previous Undertheradar interview that studying sound engineering was a pivotal point in your transition from a more music-based practice to a practice focused more specifically on sound itself. What was it about sound as phenomena, or what particular aspects of the phenomenology of sound inspired the shift in your practice?

RS: It was following the trajectory of a sound or groups of sounds around technical equipment and learning how you could adjust them, transform them, intermingle them. This allowed me to visualise sound and helped me understand it as a physical medium. I became interested in how I could arrange sounds spatially and what kinds of stories or emotional or physical effects could be created with the technology in relation to specific spaces.

JG: Do you consider sound to be material or immaterial?

RS: I consider it as being both and interconnected. The deaf percussionist Evelyn Glennie famously talks about hearing as a form of touching. It’s most noticeable when you can feel the bass vibrating your flesh or the windows. Sound is the vibration of solids, liquids or gases caused by the movement / vibration of other matter (that in turn vibrates us). I think sound bridges the material and immaterial – sound, matter, us, ideas. There’s the cultural use of sound to bridge the material / immaterial divide in spiritual belief through karakia, hymns, chanting etc. Ideas as immaterial entities are often created by specific sounds with material consequences – fear from an unexpected sound in the dark, sounds that cause stress, joy, connection etc – become (potentially) violence, illness, love, babies, political action, movement and so on to create more sounds and ideas with more material outcomes.

RS: Currently you are working with sound as a method of investigation into contemporary digital surveillance. Could you explain a bit more about your method?

JG: By employing sonification to translate data generated by surveillance technologies such as facial recognition algorithms, Twitter meta-data or internet cookies into sound I’m interested in exposing otherwise intangible monitoring infrastructures and providing an experiential platform for discussion. For example Listening Back is a plug-in for the Chrome Browser that sonifies internet cookies in real time as one browses online. By creating an audible presence for the tracking cookies that collect personal and identifying data by storing a file on your computer the plug-in functions to expose real-time digital surveillance and consequently the ways in which our everyday relationships to being surveilled have become normalised. Our access to the World Wide Web is visually mediated by screen devices and I’m interested in how sound can help us engage with phenomena beyond the strictly seen. What does sound evoke and how does it influence our understanding? By creating sonic experiential platforms of otherwise intangible phenomena how does a listening mode of examination differ from a visualisation of data or a written analysis?

RS: In making decisions in the aestheticising of your sonic data, how are you influenced by genre or the effect you want to create for an audience? What other factors influence your decision making in this area?

JG: Certain parameters and limitations are imposed by the technology I work with and therefore determine aesthetic decisions. For example with the Listening Back Chrome browser plug-in I had to limit the amount of cookies that could trigger sound at once. During the development process some websites were crashing the browser due to the sheer amount of cookie activity. Browser plug-ins were never intended to process large amounts of sound, so I had to limit the amount of cookies that can trigger sound at any one time to eighty three. In addition, the Chrome API (application programming interface) only gives developers access to each time a cookie is being inserted onto the user’s computer, deleted from the user’s computer or updated, but not how often a cookie is being read by the browser and web server. The data set I have access to is therefore determined by what information Google provides to third party developers. What was insightful to me was the extent to which certain technical processes are hidden, even from tech savvy programmers, and how these processes of online data extraction are in fact well kept business secrets

I’d like to credit Max Breedon as the tech savvy programmer I worked with on this project. Max found a way to hack into the system to access data otherwise inaccessible via the Chrome API, but I decided to play it safe since there is already an extraordinary amount of data generated by cookies being inserted, deleted or updated. Max also suggested we use the timbre.js library to generate sound. So I designed sounds via digital waveform synthesis, that is sine, saw or triangle waves, white noise and a range of effects - eq, delay, phasor, flanger, reverb. I chose four scales from which notes are randomly generated – D minor, F major, G minor, Bb major. I also chose a generic cookie sound from the library and designed specific sounds for major platforms such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Youtube, Expedia and some third party advertising cookies that are prevalent across many websites. Interestingly the Google analytics cookie is the commonest cookie embedded across the Web and our personal computers.

TT: Both of you work with the treatment of ‘found’ or recorded sound. What kind of influence does this have on the form and composition of your music? How important is this originating material to the work, or in other words, is it important that there is a truth to material in its form?

JG: For the Traced album I used sounds that had been generated from previous projects that sonified surveillance technologies. These functioned as source sounds from which I created musical pieces. In this way the research into the effects of contemporary digital surveillance forms a subtext or extended text of the musical compositions. Having said that, it is my hope and intention that the music can be experienced without the listener necessarily having knowledge of the background research that led to the creation of the source sounds. For my sonification projects I usually work with digital synthesis in MaxMSP so the sound aesthetic is determined by a digital sound and my naive programming skills. When I create music the process is very intuitive and I respond sensually to sound, which makes it difficult for me to articulate why I’ve made certain aesthetic decisions as often it just feels good to me. Of course I am also a big fan in general of drone, minimal electronic and noise. I’m also influenced by abstract music as much as traditional musical structures and the ways in which these can range from being challenging to listen to or deeply emotionally affecting.

RS: When I’m working with found sound or field recordings, I have material to edit and shape that I can use to create textures or new sonic forms. With digital tools I can zoom in isolate a grain of sound and transform it, multiply it etc, create layers upon layers that I couldn’t possibly perform in real time. In this instance the process of composition might have more to do with collage - musique concrète. In terms of keeping some kind of truth to the material - it depends on what I’m trying to do or where the recording is from. If there is some kind of responsibility to the material inherent to my having it then I will respect that responsibility. Otherwise, if I’m free to do what I want with it then I am fine with trying to create illusions, imaginary worlds, using whatever tricks I’ve got to enhance physical / emotional reactions.

Jasmine's musical career has had a long and interesting trajectory from her early minimalist explorations in the duo Minit, to several albums worth of electronic-soaked outsider folk, with a return in the last few years to some very arresting and abstract electronic arrangements informed by her research into sound as a method of investigation into contemporary digital surveillance.

Interested in providing an audible presence for phenomena that usually lie beyond human perception, via the 'sonification' of facial recognition algorithms, global networks or internet tracking cookies, she questions what it means for our personal habits to be traceable, and for our identities, choices and personalities to be reduced to streams of data. Her music draws upon influences from experimental electronic, drone, techno and the avant-garde, working with abstract sound as much as traditional musical forms, and translating data into deeply engaging, compositions.

Her album Traced made significant waves in 2017, taking, as noted by the online platform Boomkat, “the textural and spatially sensitive ambient aesthetics of her previous LP, the acclaimed Yellow Bell, into palpably more paranoid and unnerving head spaces, using her filigree appreciation of electro-acoustic dynamics to convey that feeling with a subtlety which will surely resonate with anyone aware of digital surveillance technology's transition from peripheral creep to a near ubiquitous presence.”

Auckland sound artist Rachel Shearer, who is also on Saturday's lineup, explores the medium of sound through a range of practices – recording and performance of experimental music, installation, sound design, writing, research and collaborations with practitioners of moving image and performance. Her current work has been exploring analogues of structure and pattern of ecological processes through multi-channel sound installations.

Prior to Jasmine's arrival in the country this week, she connected with Rachel via email for an exchange of ideas and approaches to their individual practices, with a question from Torben Tilly [also of Minit] thrown in for good measure!

JG: What does the term 'sound artist' mean to you?

RS: I think it’s a clunky term but it has its uses. I understand the assertion that sound is already in art so there might not be a need for the term anymore, but for those of us that work with sound most of the time it becomes a handy descriptor to help someone understand your creative practice. Maybe it communicates that you approach sound as a creative material in an exploratory manner. It draws a distinction from calling yourself a musician, as that can come with certain baggage, such as being masterful on an instrument or composing with historical musical rules. Calling yourself a sound artist might indicate that you work more closely with concepts but there’s always examples of one-liner sound art works and conceptually resonant genre musical works. Calling yourself an experimental musician is equally as useful - I use both terms depending on the context and sometimes the term sound designer is more relevant.

JG: I read in a previous Undertheradar interview that studying sound engineering was a pivotal point in your transition from a more music-based practice to a practice focused more specifically on sound itself. What was it about sound as phenomena, or what particular aspects of the phenomenology of sound inspired the shift in your practice?

RS: It was following the trajectory of a sound or groups of sounds around technical equipment and learning how you could adjust them, transform them, intermingle them. This allowed me to visualise sound and helped me understand it as a physical medium. I became interested in how I could arrange sounds spatially and what kinds of stories or emotional or physical effects could be created with the technology in relation to specific spaces.

JG: Do you consider sound to be material or immaterial?

RS: I consider it as being both and interconnected. The deaf percussionist Evelyn Glennie famously talks about hearing as a form of touching. It’s most noticeable when you can feel the bass vibrating your flesh or the windows. Sound is the vibration of solids, liquids or gases caused by the movement / vibration of other matter (that in turn vibrates us). I think sound bridges the material and immaterial – sound, matter, us, ideas. There’s the cultural use of sound to bridge the material / immaterial divide in spiritual belief through karakia, hymns, chanting etc. Ideas as immaterial entities are often created by specific sounds with material consequences – fear from an unexpected sound in the dark, sounds that cause stress, joy, connection etc – become (potentially) violence, illness, love, babies, political action, movement and so on to create more sounds and ideas with more material outcomes.

RS: Currently you are working with sound as a method of investigation into contemporary digital surveillance. Could you explain a bit more about your method?

JG: By employing sonification to translate data generated by surveillance technologies such as facial recognition algorithms, Twitter meta-data or internet cookies into sound I’m interested in exposing otherwise intangible monitoring infrastructures and providing an experiential platform for discussion. For example Listening Back is a plug-in for the Chrome Browser that sonifies internet cookies in real time as one browses online. By creating an audible presence for the tracking cookies that collect personal and identifying data by storing a file on your computer the plug-in functions to expose real-time digital surveillance and consequently the ways in which our everyday relationships to being surveilled have become normalised. Our access to the World Wide Web is visually mediated by screen devices and I’m interested in how sound can help us engage with phenomena beyond the strictly seen. What does sound evoke and how does it influence our understanding? By creating sonic experiential platforms of otherwise intangible phenomena how does a listening mode of examination differ from a visualisation of data or a written analysis?

RS: In making decisions in the aestheticising of your sonic data, how are you influenced by genre or the effect you want to create for an audience? What other factors influence your decision making in this area?

JG: Certain parameters and limitations are imposed by the technology I work with and therefore determine aesthetic decisions. For example with the Listening Back Chrome browser plug-in I had to limit the amount of cookies that could trigger sound at once. During the development process some websites were crashing the browser due to the sheer amount of cookie activity. Browser plug-ins were never intended to process large amounts of sound, so I had to limit the amount of cookies that can trigger sound at any one time to eighty three. In addition, the Chrome API (application programming interface) only gives developers access to each time a cookie is being inserted onto the user’s computer, deleted from the user’s computer or updated, but not how often a cookie is being read by the browser and web server. The data set I have access to is therefore determined by what information Google provides to third party developers. What was insightful to me was the extent to which certain technical processes are hidden, even from tech savvy programmers, and how these processes of online data extraction are in fact well kept business secrets

I’d like to credit Max Breedon as the tech savvy programmer I worked with on this project. Max found a way to hack into the system to access data otherwise inaccessible via the Chrome API, but I decided to play it safe since there is already an extraordinary amount of data generated by cookies being inserted, deleted or updated. Max also suggested we use the timbre.js library to generate sound. So I designed sounds via digital waveform synthesis, that is sine, saw or triangle waves, white noise and a range of effects - eq, delay, phasor, flanger, reverb. I chose four scales from which notes are randomly generated – D minor, F major, G minor, Bb major. I also chose a generic cookie sound from the library and designed specific sounds for major platforms such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Youtube, Expedia and some third party advertising cookies that are prevalent across many websites. Interestingly the Google analytics cookie is the commonest cookie embedded across the Web and our personal computers.

TT: Both of you work with the treatment of ‘found’ or recorded sound. What kind of influence does this have on the form and composition of your music? How important is this originating material to the work, or in other words, is it important that there is a truth to material in its form?

JG: For the Traced album I used sounds that had been generated from previous projects that sonified surveillance technologies. These functioned as source sounds from which I created musical pieces. In this way the research into the effects of contemporary digital surveillance forms a subtext or extended text of the musical compositions. Having said that, it is my hope and intention that the music can be experienced without the listener necessarily having knowledge of the background research that led to the creation of the source sounds. For my sonification projects I usually work with digital synthesis in MaxMSP so the sound aesthetic is determined by a digital sound and my naive programming skills. When I create music the process is very intuitive and I respond sensually to sound, which makes it difficult for me to articulate why I’ve made certain aesthetic decisions as often it just feels good to me. Of course I am also a big fan in general of drone, minimal electronic and noise. I’m also influenced by abstract music as much as traditional musical structures and the ways in which these can range from being challenging to listen to or deeply emotionally affecting.

RS: When I’m working with found sound or field recordings, I have material to edit and shape that I can use to create textures or new sonic forms. With digital tools I can zoom in isolate a grain of sound and transform it, multiply it etc, create layers upon layers that I couldn’t possibly perform in real time. In this instance the process of composition might have more to do with collage - musique concrète. In terms of keeping some kind of truth to the material - it depends on what I’m trying to do or where the recording is from. If there is some kind of responsibility to the material inherent to my having it then I will respect that responsibility. Otherwise, if I’m free to do what I want with it then I am fine with trying to create illusions, imaginary worlds, using whatever tricks I’ve got to enhance physical / emotional reactions.

Jasmine Guffond

Jasmine Guffond

Minit

Rachel Shearer