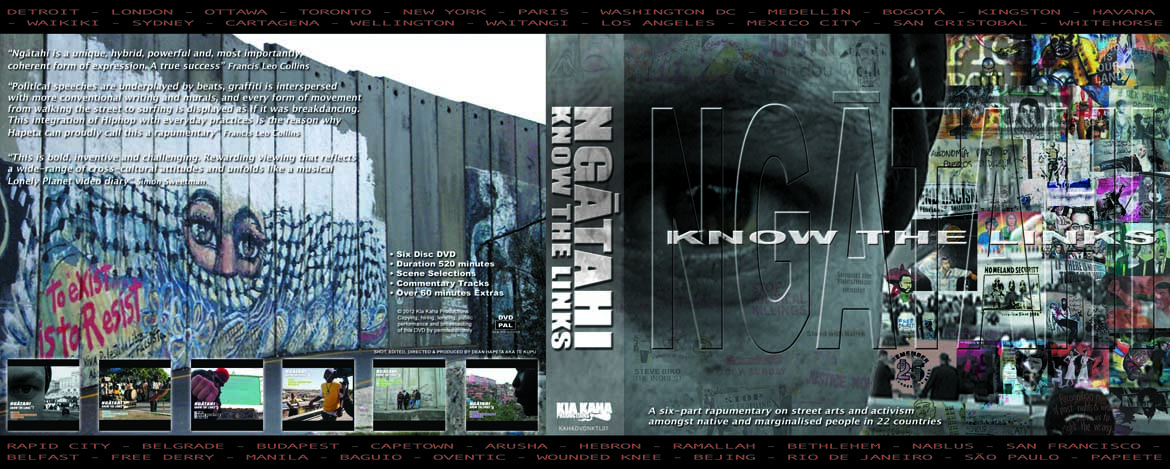

NGĀTAHI: Know The Links

By Dr. Francis Collins

The idea of empowerment is not easy to pin down, it is about

justice and recognition, it demands self-determination, but it also

crucially hinges on knowledge and expression. We cannot achieve

empowerment without some sense of what it is we are trying to

achieve, without specifying the domains of power that shape our

worlds and without always questioning the social injustices that surround us.1 Empowerment also demands expression, projecting different voices and experiences in different ways, and always being

open to alternative possibilities for the future. Te Kupu’s monumental ‘rapumentary’ Ngātahi: Know the Links sets out to capture this intersection of empowerment, knowledge and expression as it emerges

in cities, dancehalls and villages across the planet. In no less than

six DVDs and 520 minutes, Te Kupu explores street arts and activism across the world, drawing attention to systems and processes of

marginalisation and discrimination as well as the work of artists and

activists who would transform these conditions.

Te Kupu, a.k.a. Dean Hapeta and front man of Aotearoa crew Upper Hutt Posse, took over ten years to complete this mammoth project, beginning with filming of parts 1 and 2 in the year 2000 (released initially in 2004) and concluding with the filming of Part 6 in 2011. Even across this length of time, assembling the diversity of voices and ideas that come together in Ngātahi is an extraordinary achievement in itself. The rapumentary takes its viewers through cities and settlements across Canada, USA, France and Colombia (Part 1); Ja- maica, Cuba, Australia, Hawai’i, Colombia and Aotearoa (Part 2); USA, Mexico, and Canada (Part 3); South Africa, Tanzania and Ta- hiti (Part 4); Palestine, Ireland and Philippines (Part 5); Hungary, Serbia, Brazil, China and finally to New York (Part 6). The connections that Te Kupu has used and established through this journey are simply extraordinary; they demonstrate the breadth and depth of Hip Hop culture across the planet and its status as perhaps the most sustained form of alter-globalisation.2

Ngātahi means to stand together, to be as one and to act in unison. It also draws attention to linkages between people and places, to shared circumstances and to often under-recognised connections, it asks that we Know the Links. With this focus on interconnections and solidarity in mind, Te Kupu carefully crafts a set of diverse narratives and voices together, that demonstrate the ways in which contemporary systems of marginalisation have emerged over longer histories but also through remarkably similar processes in different parts of the world. This is particularly apparent in the many Indigenous struggles that are captured in Ngātahi, the shared ways in which colonisation has and continues to shape present circumstances. Imperialism and colonialism loom large here, then, as overarching structures that have shaped contemporary racial politics across the world, and led to socio-political situations where Indigenous and minoritised groups encounter remarkably similar forces of exclusion from but also pressure to assimilate into society. These ongoing power dynamics are then overlaid by consumerist forms of globalisation that encourage identification through the consumption of corporate culture rather than knowledge of culture and history.

Parts 1 and 2 were filmed in the early 2000s and released on DVD in 2004 and presented at the Sundance Film Festival in that year. I recall encountering and reviewing3 this first release and in the process being struck by the power of Te Kupu’s narrative, by the fervent post or more aptly anti-colonialism and by the determination to draw attention to the under-recognised connections between peoples and places. The emphasis on Hip Hop arts, culture and attitude is also particularly striking in these first volumes, featuring significantly as a focus on screen but also influencing the style of production in the soundtrack, tempo and camera angles. We encounter Rashid in Detroit who highlights the racial hierarchies that constituted the making of America; Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm in Toronto discussing the tactics that are used everywhere to displace and disenfranchise Indigenous and minoritised peoples; and Hone Harawira and Moana Jackson in Aotearoa demonstrating the ongoing processes of colonisation. Viewed in relation to the rest of the box-set these first two parts also very successfully establish the critical narrative of Te Kupu’s endeavour, that “one of the most powerful weapons is an open mind”. The message here is that in order to alter our current situation we must learn about the connections between oppression in different places, to understand how history shapes the present, and develop knowledge as a tool for empowerment rather than further repression, we must be open to new ideas that can reshape the worlds we live in.

Traversing the Americas from Chiapas to Whitehorse, Part 3 takes us on one such journey of learning about the connections that are paradoxically part of drawing boundaries and separating people in the world. We begin in Los Angeles with the music of Aztlan Underground and the splicing of scenes of urban lives of wealth and poverty that demonstrate the results of contemporary political-economic systems. Echoing these contemporary borders, that are themselves the product of specific practices of disenfranchisement, Aztlan Underground remind us of a pre-Colombian Americas where the legal, and indeed mental, borders of today did not exist. These borders separate Indigenous peoples, create conditions for slavery and establish the basis for ongoing colonisation through globalised consumerism. We are shown how colonisation has disconnected indigenous peoples from their land in Whitehorse (Canada) and Wounded Knee (USA) and undermined their cultures in a way that means young people don’t have an opportunity to learn about their own histories. The response to these shared conditions here, and by the Zapatistas in the Chiapas, is to create new spaces of independence through self-government, schools and a willingness to resist ongoing colonisation, to envision different possibilities for the future.

The ‘colonial present’4 emerges in particularly stark ways in Parts 4 and 5, which traverse the apartheid geographies of South Africa and Palestine and the still colonial Tahiti and Ireland. From the luxury of gated communities inhabited by still privileged white populations to the peripheral spaces of black life, the exploration of Cape Town demonstrates that the distinctions that characterised apartheid remain as strong as ever. Rather than legal borders, it is now financial apartheid and discrimination that marginalises non-whites, a situation where flowery rhetoric promotes a vision of multicultural harmony while the brute force of the government and capitalism reinforces segregation and exclusion. The connections to the walling of Palestine are more than obvious. The Israeli exclusion wall has not only changed the ability for Palestinians to move but it has also generated a material and psychological reminder of the active separation of people from land. In both these contexts, Ngātahi also brings us up close with the vibrancy of culture, with the role of hip hop and other musical and art forms in expressing these conditions of marginalisation but also articulating alternative identities and aspirations for justice. So too it is in Ireland, where music (if not Hip Hop) plays a big role in politics, and art helps us to understand the connections between places. We are shown the ‘International Wall’ in Belfast, where struggles against colonialism across the world are identified for solidarity, highlighting that “there’s a common struggle for everyone and that’s the right to be free”.

The final instalment in Part 6 draws the viewer back to the key connections between people and places and the importance of knowledge in empowerment. We begin in Budapest and Belgrade with the situation of Roma peoples who are consistently excluded from the various European societies they should be part of, unable to find secure employment, displaced through demolition of informal housing, and discriminated against in daily life. Their circumstances reflect both racism and the impact of national bor- ders in separating people who are spread across a continent. This is brought into stark relief by the desire amongst older Roma for the days of communism, where as part of the forced assimilation of peoples distinctions were made less apparent and everyone had a job. Capitalism, of course, works through such differences – separating people and generating inequality through race, class, gender, language, religion and many other differences. In the favelas that sit above Copacabana beach in Rio these differences are amplified, between the spectacular shoreline of the city and the exclusion of black and other peoples in hills above, where access to schools, housing and other basic needs are difficult. The response here comes in the form of rights movements, but also strategies for survival in the peripheries and of course the strength that can be generated in music and arts, particularly hip hop. Indeed, as KRS-One, the ‘conscience of hip hop’5, declares in the final moments, Hip Hop is not just about rap and the cultures that originated in the Bronx, but is rather about activism, it is about self-determination, and most importantly attitude.

Te Kupu, a.k.a. Dean Hapeta and front man of Aotearoa crew Upper Hutt Posse, took over ten years to complete this mammoth project, beginning with filming of parts 1 and 2 in the year 2000 (released initially in 2004) and concluding with the filming of Part 6 in 2011. Even across this length of time, assembling the diversity of voices and ideas that come together in Ngātahi is an extraordinary achievement in itself. The rapumentary takes its viewers through cities and settlements across Canada, USA, France and Colombia (Part 1); Ja- maica, Cuba, Australia, Hawai’i, Colombia and Aotearoa (Part 2); USA, Mexico, and Canada (Part 3); South Africa, Tanzania and Ta- hiti (Part 4); Palestine, Ireland and Philippines (Part 5); Hungary, Serbia, Brazil, China and finally to New York (Part 6). The connections that Te Kupu has used and established through this journey are simply extraordinary; they demonstrate the breadth and depth of Hip Hop culture across the planet and its status as perhaps the most sustained form of alter-globalisation.2

Ngātahi means to stand together, to be as one and to act in unison. It also draws attention to linkages between people and places, to shared circumstances and to often under-recognised connections, it asks that we Know the Links. With this focus on interconnections and solidarity in mind, Te Kupu carefully crafts a set of diverse narratives and voices together, that demonstrate the ways in which contemporary systems of marginalisation have emerged over longer histories but also through remarkably similar processes in different parts of the world. This is particularly apparent in the many Indigenous struggles that are captured in Ngātahi, the shared ways in which colonisation has and continues to shape present circumstances. Imperialism and colonialism loom large here, then, as overarching structures that have shaped contemporary racial politics across the world, and led to socio-political situations where Indigenous and minoritised groups encounter remarkably similar forces of exclusion from but also pressure to assimilate into society. These ongoing power dynamics are then overlaid by consumerist forms of globalisation that encourage identification through the consumption of corporate culture rather than knowledge of culture and history.

Parts 1 and 2 were filmed in the early 2000s and released on DVD in 2004 and presented at the Sundance Film Festival in that year. I recall encountering and reviewing3 this first release and in the process being struck by the power of Te Kupu’s narrative, by the fervent post or more aptly anti-colonialism and by the determination to draw attention to the under-recognised connections between peoples and places. The emphasis on Hip Hop arts, culture and attitude is also particularly striking in these first volumes, featuring significantly as a focus on screen but also influencing the style of production in the soundtrack, tempo and camera angles. We encounter Rashid in Detroit who highlights the racial hierarchies that constituted the making of America; Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm in Toronto discussing the tactics that are used everywhere to displace and disenfranchise Indigenous and minoritised peoples; and Hone Harawira and Moana Jackson in Aotearoa demonstrating the ongoing processes of colonisation. Viewed in relation to the rest of the box-set these first two parts also very successfully establish the critical narrative of Te Kupu’s endeavour, that “one of the most powerful weapons is an open mind”. The message here is that in order to alter our current situation we must learn about the connections between oppression in different places, to understand how history shapes the present, and develop knowledge as a tool for empowerment rather than further repression, we must be open to new ideas that can reshape the worlds we live in.

Traversing the Americas from Chiapas to Whitehorse, Part 3 takes us on one such journey of learning about the connections that are paradoxically part of drawing boundaries and separating people in the world. We begin in Los Angeles with the music of Aztlan Underground and the splicing of scenes of urban lives of wealth and poverty that demonstrate the results of contemporary political-economic systems. Echoing these contemporary borders, that are themselves the product of specific practices of disenfranchisement, Aztlan Underground remind us of a pre-Colombian Americas where the legal, and indeed mental, borders of today did not exist. These borders separate Indigenous peoples, create conditions for slavery and establish the basis for ongoing colonisation through globalised consumerism. We are shown how colonisation has disconnected indigenous peoples from their land in Whitehorse (Canada) and Wounded Knee (USA) and undermined their cultures in a way that means young people don’t have an opportunity to learn about their own histories. The response to these shared conditions here, and by the Zapatistas in the Chiapas, is to create new spaces of independence through self-government, schools and a willingness to resist ongoing colonisation, to envision different possibilities for the future.

The ‘colonial present’4 emerges in particularly stark ways in Parts 4 and 5, which traverse the apartheid geographies of South Africa and Palestine and the still colonial Tahiti and Ireland. From the luxury of gated communities inhabited by still privileged white populations to the peripheral spaces of black life, the exploration of Cape Town demonstrates that the distinctions that characterised apartheid remain as strong as ever. Rather than legal borders, it is now financial apartheid and discrimination that marginalises non-whites, a situation where flowery rhetoric promotes a vision of multicultural harmony while the brute force of the government and capitalism reinforces segregation and exclusion. The connections to the walling of Palestine are more than obvious. The Israeli exclusion wall has not only changed the ability for Palestinians to move but it has also generated a material and psychological reminder of the active separation of people from land. In both these contexts, Ngātahi also brings us up close with the vibrancy of culture, with the role of hip hop and other musical and art forms in expressing these conditions of marginalisation but also articulating alternative identities and aspirations for justice. So too it is in Ireland, where music (if not Hip Hop) plays a big role in politics, and art helps us to understand the connections between places. We are shown the ‘International Wall’ in Belfast, where struggles against colonialism across the world are identified for solidarity, highlighting that “there’s a common struggle for everyone and that’s the right to be free”.

The final instalment in Part 6 draws the viewer back to the key connections between people and places and the importance of knowledge in empowerment. We begin in Budapest and Belgrade with the situation of Roma peoples who are consistently excluded from the various European societies they should be part of, unable to find secure employment, displaced through demolition of informal housing, and discriminated against in daily life. Their circumstances reflect both racism and the impact of national bor- ders in separating people who are spread across a continent. This is brought into stark relief by the desire amongst older Roma for the days of communism, where as part of the forced assimilation of peoples distinctions were made less apparent and everyone had a job. Capitalism, of course, works through such differences – separating people and generating inequality through race, class, gender, language, religion and many other differences. In the favelas that sit above Copacabana beach in Rio these differences are amplified, between the spectacular shoreline of the city and the exclusion of black and other peoples in hills above, where access to schools, housing and other basic needs are difficult. The response here comes in the form of rights movements, but also strategies for survival in the peripheries and of course the strength that can be generated in music and arts, particularly hip hop. Indeed, as KRS-One, the ‘conscience of hip hop’5, declares in the final moments, Hip Hop is not just about rap and the cultures that originated in the Bronx, but is rather about activism, it is about self-determination, and most importantly attitude.

Born in Upper Hutt, 1966, Dean Hapeta a.k.a D Word a.k.a. Te Kupu has been producing south pacific indigenous rap and reggae for 15 years. From 1985 he has been the driving force behind Upper Hutt Posse which formed at that time as a four piece reggae group.

Known for his strong political views which permeate his and Upper Hutt Posse’s music, Te Kupu is a pioneer in the local music scene responsible for the composition and production of Aotearoa’s first rap record. With his involvement in 12 separate music videos as producer and/or director and/or editor, Te Kupu’s work has extended into the visual domain where he is equally as outspoken and at hone as in the world of music.

In creating this monumental anti-monument, Ngātahi - Know the Links, Te Kupu travelled to Australia, USA, Canada and Rarotonga, performing both with UHP and as a solo artist along the way. In 2000 he visited USA, Canada, England and France to continue film- ing the ‘rap-u-mentary’, first premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. This massive body of work addresses the socio-political consciousness of oppressed peoples taking their involvement in Hip Hop culture and music as a point of denture. Over six DVDs and over 500 minutes, Te Kupu weaves for us a story of Hip Hop as the alter-modern answer to colonial-capitalism.

Francis is based at The University of Auckland where he spends his time researching and writing on migration, cities, labour, desire, time and futures. Research, writing and other stuff can be found at: https://movingfutures.wordpress.com/

While Te Kupu is careful to show the ways in which these processes articulate in a wide variety of landscapes, Ngātahi is very much

about cities. Indeed, the urban fabric and urban politics are in many

respects one of the most central and consistent characters throughout the box set. The camera takes us through countless streets, alleys,

apartment buildings, favelas and settlements, always taking the view

from the ground, letting the street speak for itself. We walk, drive in

cars and ride on motorbikes through all these spaces, feeling the fluidity and mobility of the city but also the way it changes and the way

that the built environment manifests marginalisation as well as the

practices and technologies of resistance. Hip Hop itself is very much

an urban culture of the highest degree, shaped by the various places

it emerges in and the conditions of those who participate. It emerges

as response to the urban conditions of marginalised peoples, like the

segment in Paris (Part 1) where young black men are harassed by

police in the streets and excluded from what it means to be French.

But the urban fabric is also part of hip hop’s activism and attitude,

the liberating spaces of radio, the infectious sounds of ‘reprsenta’

and the remaking of urban form through graffiti. So while we often

encounter the urban periphery in Ngātahi we are also always shown

how something more is possible in this space, how through hip hop

and other cultural forms the city can be remade.

The urban periphery, then, may well be a place of exclusion but it can also be the basis for making the world differently; as post- colonial urbanist AbdouMaliq Simone suggests it is “a generative space— a source of innovation and adaptation”.6 In each of the places Te Kupu visits through Ngātahi, people are not only expressing their situations and challenging their marginalisation but they are also finding new ways of living that refuse to be limited by circumstance. These peripheral cultures manifest in a whole range of ways.

There is the open studio and art-space in the favelas above Copacabana in Rio (Part 6), which provide young people with an opportunity to engage in activities that take them away from drugs and crime. In Capetown (Part 4) we are introduced to the open-access digital art of Mustafa Maluka and the ‘Street Parliament’ music collaboration that provide alternative voices to the commercialisation of mu- sic and culture. Or, in Aotearoa (Part 2), Budapest (Part 6), Manila (Part 5) and Washington DC (Part 1) we are shown how collective action is part of providing recognition to marginalised groups and asserting social justice as a central pillar of life.

Hip Hop is both the medium and the message of Ngātahi. It is an art form that brings people together from diverse locales, it is a way of life that challenges governmental and institutional structures, and it is an attitude that promises to reconfigure the world we inhabit. In making this ‘rapumentary’ Te Kupu has crafted a unique and powerful composition that demonstrates the rhythms of everyday life and the beats of political acts. His journey across the world often occurs through encounters with hip-hop artists, but they also lead to poetry, reggae, folk, traditional music and other forms of expression. Through this diversity of textures, Te Kupu weaves a Hip Hop thread that is loud and clear, speeches are underplayed with beats, graffiti is interspersed with other art forms and movement of all kinds is re-presented as dance. This is the medium that makes Ngātahi a rapumentary. Hip Hop is also the message, or more importantly ‘the attitude’ as KRS-One describes in the final scenes of Part 6, it is “the transformation of subjects and objects in an attempt to transform your inner being, to express your inner being”. The outcome is that rather than just being shaped by the environments and situations we live in, Hip Hop is about telling the environment what we want it to be, it is about claiming a right to recreate the world after our own desires.7 Ngātahi shows us that this is not only a possibility for the future but is rather a requirement and reality of the present.

The urban periphery, then, may well be a place of exclusion but it can also be the basis for making the world differently; as post- colonial urbanist AbdouMaliq Simone suggests it is “a generative space— a source of innovation and adaptation”.6 In each of the places Te Kupu visits through Ngātahi, people are not only expressing their situations and challenging their marginalisation but they are also finding new ways of living that refuse to be limited by circumstance. These peripheral cultures manifest in a whole range of ways.

There is the open studio and art-space in the favelas above Copacabana in Rio (Part 6), which provide young people with an opportunity to engage in activities that take them away from drugs and crime. In Capetown (Part 4) we are introduced to the open-access digital art of Mustafa Maluka and the ‘Street Parliament’ music collaboration that provide alternative voices to the commercialisation of mu- sic and culture. Or, in Aotearoa (Part 2), Budapest (Part 6), Manila (Part 5) and Washington DC (Part 1) we are shown how collective action is part of providing recognition to marginalised groups and asserting social justice as a central pillar of life.

Hip Hop is both the medium and the message of Ngātahi. It is an art form that brings people together from diverse locales, it is a way of life that challenges governmental and institutional structures, and it is an attitude that promises to reconfigure the world we inhabit. In making this ‘rapumentary’ Te Kupu has crafted a unique and powerful composition that demonstrates the rhythms of everyday life and the beats of political acts. His journey across the world often occurs through encounters with hip-hop artists, but they also lead to poetry, reggae, folk, traditional music and other forms of expression. Through this diversity of textures, Te Kupu weaves a Hip Hop thread that is loud and clear, speeches are underplayed with beats, graffiti is interspersed with other art forms and movement of all kinds is re-presented as dance. This is the medium that makes Ngātahi a rapumentary. Hip Hop is also the message, or more importantly ‘the attitude’ as KRS-One describes in the final scenes of Part 6, it is “the transformation of subjects and objects in an attempt to transform your inner being, to express your inner being”. The outcome is that rather than just being shaped by the environments and situations we live in, Hip Hop is about telling the environment what we want it to be, it is about claiming a right to recreate the world after our own desires.7 Ngātahi shows us that this is not only a possibility for the future but is rather a requirement and reality of the present.

1. This is the all-embracing ‘politics of empowerment’ articulated by Patricia Hill

Collins, a recognition of the generation of empowerment in the struggle for justice

and different worlds. See: Collins, P.H. (2000), Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge

Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment, Routledge: New York.

2. I use the term ‘alter-globalization’ to refer here to global networks and relations that are not determined by corporate and governmental interests in advance, but rather emerge through the generation of an international public space. Hip Hop represents one excellent example ordinarily, but in particular in the way in which Te Kupu presents it in Ngātahi, he has literally travelled through the networks of Hip Hop across the world, following but also then manifesting this truly global culture in his journeys. See: Pleyers, G. (2010), Alter- Globalization: Becoming Actors in a Global Age, Polity Presss: Cambridge.

3. See: Collins, F.L. (2006), ‘Review: Ngātahi: Know the Links’, Graduate Journal

of Asia-Pacific Studies, 2(1): 95-96. https://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/arts/Depart- ments/asian-studies/gjaps/docs- vol2/Collins1.pdf

4. The ‘colonial present’ is a term used by the critical geographer Derek Gregory in his book of the same name. It draws attention to the continuing role of colonialism in shaping the world we live in, not just in the most materially apparent ways such as in places like Palestine but indeed through the lives of the marginalized across the planet. See: Gregory, D. (2004), The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq, Blackwell.

5. See: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/krs-one

6. Abdou-Maliq Simone, like Te Kupu, focuses on demonstrating the linkages across diverse urban settings in his book City Life from Jakarta to Dakar, showing in particular how marginalization occurs but also how people remake their worlds through the opportunities that are available in the periphery. See: Simone (2010), City Life from Jakarta to Dakar: Movements at the Crossroads, Routlede: London, p.41.

7. In this way, we might also understand Hip Hop as a fundamental expression

of ‘the right to the city’ or the right to space more generally, a politics that draws attention not just to having access to urban life, but rather to participating and appropriating the spaces within which we live. See: Harvey, D. (2012), Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, Verso: London.

2. I use the term ‘alter-globalization’ to refer here to global networks and relations that are not determined by corporate and governmental interests in advance, but rather emerge through the generation of an international public space. Hip Hop represents one excellent example ordinarily, but in particular in the way in which Te Kupu presents it in Ngātahi, he has literally travelled through the networks of Hip Hop across the world, following but also then manifesting this truly global culture in his journeys. See: Pleyers, G. (2010), Alter- Globalization: Becoming Actors in a Global Age, Polity Presss: Cambridge.

3. See: Collins, F.L. (2006), ‘Review: Ngātahi: Know the Links’, Graduate Journal

of Asia-Pacific Studies, 2(1): 95-96. https://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/arts/Depart- ments/asian-studies/gjaps/docs- vol2/Collins1.pdf

4. The ‘colonial present’ is a term used by the critical geographer Derek Gregory in his book of the same name. It draws attention to the continuing role of colonialism in shaping the world we live in, not just in the most materially apparent ways such as in places like Palestine but indeed through the lives of the marginalized across the planet. See: Gregory, D. (2004), The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq, Blackwell.

5. See: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/krs-one

6. Abdou-Maliq Simone, like Te Kupu, focuses on demonstrating the linkages across diverse urban settings in his book City Life from Jakarta to Dakar, showing in particular how marginalization occurs but also how people remake their worlds through the opportunities that are available in the periphery. See: Simone (2010), City Life from Jakarta to Dakar: Movements at the Crossroads, Routlede: London, p.41.

7. In this way, we might also understand Hip Hop as a fundamental expression

of ‘the right to the city’ or the right to space more generally, a politics that draws attention not just to having access to urban life, but rather to participating and appropriating the spaces within which we live. See: Harvey, D. (2012), Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution, Verso: London.